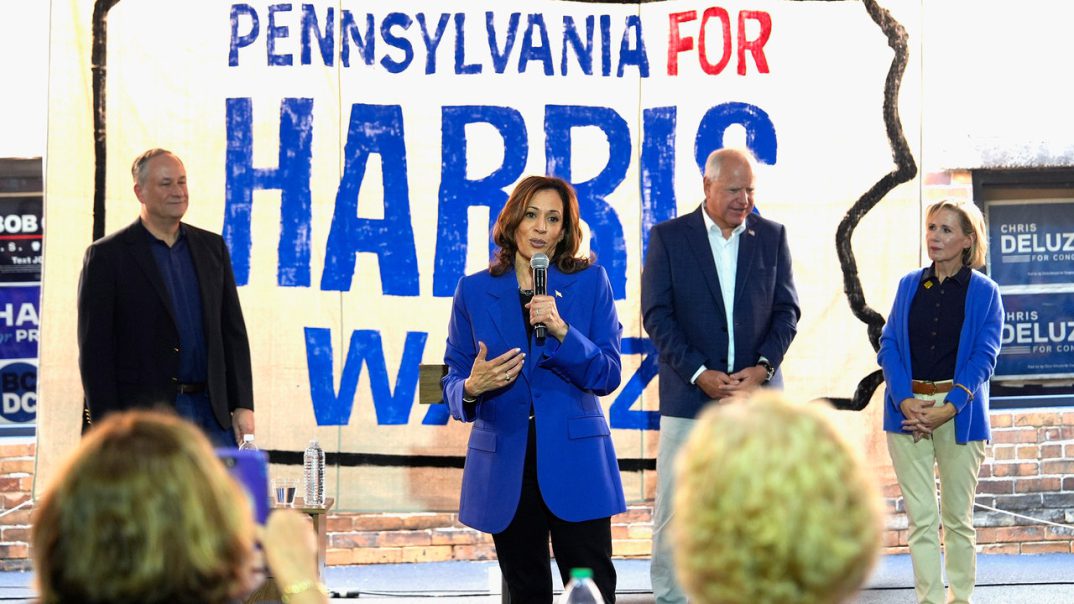

One recent Sunday, a young organizer named Daniel Zevallos sat in Kamala Harris’s campaign office in Allentown, Pennsylvania. The office, hastily set up in a former home-health-care agency, opened on August 11th, and the grand opening’s silver balloons and paper garlands were still hanging. From his post, Zevallos could see a countdown calendar, reminding him that less than two months remained before the election. Hunched over his laptop, he surveyed local maps, which showed that Republicans had made sizable inroads with the state’s Latinos in recent years. Even though Donald Trump lost Pennsylvania in 2020, after winning it in 2016, he increased the number of votes he received in Allentown by twenty-two per cent.

Zevallos’s father, who is Peruvian, came to Allentown as part of a wave of Latino immigrants that has transformed the town in recent decades. In an earlier age, Allentown had been the Queen City of the Lehigh Valley, distinguished by the miles of silk mills and foundries where generations of Germans and Italians came to work. As the region’s industry decayed, the foundries shed workers and the streets emptied out. Over time, though, a new set of companies attracted a workforce of mainly Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, and Mexicans. Today, Allentown is a crucial node in Pennsylvania’s so-called Latino Belt—a smattering of cities with just enough Latino voters to tip the state.

Zevallos learned the political terrain early. During high school, he volunteered for Bernie Sanders, knocking on as many as a hundred and fifty doors a day. In Pennsylvania, such numbers could make a difference; elections were often won and lost by tiny margins. In 2020, Joe Biden carried the state by less than eighty-two thousand votes—just over one per cent of the total.

At the office, a small group of New Yorkers who had come to canvass were going through a checklist of tips, which culminated in “Don’t forget your smile.” The group had driven more than a hundred miles to be there. “I’ve been inviting all of my friends!” a woman declared. Zevallos said that more people were signing up to volunteer these days and stopping by to ask how they could get involved. “There’s a lot more enthusiasm from the rank and file,” he said, as he grabbed a sheaf of flyers and a list of doors to knock on.

The city’s downtown is made up mostly of small, tightly packed row houses. “You can do two hundred or two hundred fifty a day, if you’re really trying,” Zevallos said. He had learned that the key to canvassing was gentle insistence. “Just here for Vice-President Harris!” he’d say, after the first knock. “Will you be voting this year? Do you know who you’re voting for?”

The answers he got revealed an electorate that was at best mildly engaged by the election. On one porch, a man in cargo shorts and rubber sandals said, “Honestly, I’m, like, fed up with the politics thing.” Next door, a young woman in pink leopard pajamas said, “Oh, I’m not voting.” Down the block, a man with a thick mustache told Zevallos, “I’m in the middle of prepping food.” He wiped his hands, which were smeared with oil. “It’s politics—I generally don’t discuss it with people,” he said. “It’s kind of like religion, two subjects that I was taught you never discuss.”

Harris’s advisers like to say that she built her career in California, the state with the country’s largest Latino population, and understands how to court this electorate. In 2010, when she became the attorney general of California, she earned support from a majority of Latinos—and did so again when she ran for reëlection, four years later. In the race to represent California in the U.S. Senate, she comfortably defeated Loretta Sanchez, a Democrat of Mexican descent. But whether those statewide victories suggest that she can win over an electorate of more than thirty-six million, whose particularities vary by geography and origin, is still an open question.

In her first ad targeting Latinos, Harris highlighted her immigrant roots, praising the influence of her mother, who left India at the age of nineteen, and describing the effort it took for Harris to go from a summer job at McDonald’s to the San Francisco district attorney’s office and eventually to the Vice-Presidency. “With that same determination,” a narrator says with a subtly accented voice, “she always defended us.” But it wasn’t quite clear who “us” referred to, let alone whether it was Latino swing voters. Mike Madrid, a co-founder of the Lincoln Project, argued that the ad spoke to first- and second-generation Latinos, who were already solidly Democratic. “This is not where Democrats have a problem,” he said. Third- and fourth-generation voters, particularly men without a college degree, “those are the voters they’ve been hemorrhaging.”

Another campaign ad, titled “Tougher,” takes a different tack, highlighting Harris’s early career as a prosecutor taking on drug cartels. It also touts her support for a notably conservative border-security agreement, which Republicans helped craft (and ultimately blocked, as Trump worked to avoid a victory for the Democrats). The mention of the agreement was a departure from the Democratic Party’s traditional message on immigration, which favored humanitarian policies over enforcement.

Madrid argued that immigration was the wrong focus in any case. “It has never been a litmus-test issue, the way that the Democrats—and the Republicans, for that matter—leaned into it,” he said. “Latinos have been screaming at the top of their lungs, We want an economic agenda, we want a jobs agenda, we want an affordability agenda. What did they get? They get immigration reform.” One of Harris’s first major policy proposals showed some awareness of these concerns; it was an ambitious initiative to address the housing crisis, including proposals to build three million homes in the next four years. “One in five Latino men are employed in the residential-construction industry, or a related field,” Madrid said. “They have been hammered, at a time when interest rates have tripled since the Trump Administration.”

Just before Biden ended his campaign, a Pew poll showed that he and Trump were in a virtual tie among Latinos in battleground states—a disastrous finding for a party that has historically secured nearly two-thirds of the Latino vote. After Harris announced her candidacy, early polling showed that she held an eighteen-point lead over Trump.

Chuck Rocha, a leading Democratic consultant, said that Harris’s age, along with the basic positivity of her campaign, played to her favor; the Latino electorate is overwhelmingly young, with nearly a third of voters under the age of thirty. “Having this campaign rooted almost in joy and optimism, compared to the hate and viciousness that they see from the Republicans, is a stark contrast,” Rocha said. A major poll of Latinos, released earlier this month by the group UnidosUS, shows that voters were most concerned with pocketbook issues: inflation, wages, the cost of housing and health care. “Latinos are misunderstood sometimes as not being as aspirational as other sectors,” Rocha said. As he put it, they want to know, “What will you do pretty immediately to make my life better?”

As part of Zevallos’s outreach, he met with Norberto Dominguez, a revered community leader. Dominguez, who is fifty-seven, had been living in Allentown since the seventies; his family had arrived there after fleeing the Trujillo dictatorship, in the Dominican Republic. “My father, being a steelworker, did what most Latinos do—he worked hard and saved up to buy a house,” Dominguez said. Growing up, Dominguez was one of just a handful of Latinos enrolled at William Allen High School, but a huge influx followed. “In the past seven to ten years, we’ve seen a third wave, and it’s really boomed,” Dominguez said. The city is now majority Latino, and recently elected its first Latino mayor.

“Half my family is Democrat, the other half is Republican,” Dominguez went on. The G.O.P.’s appeal among Latinos was growing all around him—his cousins and brothers had a particular affinity for Trump. “Men are attracted to men who make money,” Dominguez said. “The caveman comes back at us.” But, Dominguez noted, Trump also had a unique ability to turn away historically conservative voters. “The portion of independents in the family is growing,” he said.

One of Trump’s persistent attack lines has been to link Harris to the Biden Administration’s handling of immigration. But respondents to the UnidosUS poll seemed to align with her policies, clearly supporting a path to citizenship for immigrants with deep roots in the country and rejecting the mass-deportation initiatives that Trump has proposed. On the economy, as on immigration, Latinos overwhelmingly said that the Democratic Party represented their views. Abortion provides an especially pronounced advantage for Harris; asked whether they believed that it was “wrong to make abortion illegal and take that choice away,” seventy-one per cent of respondents said that they did.

Over all, Harris holds a lead in the high twenties—a marked improvement, but short of the thirty-point margin that helped carry Biden to victory in 2020. To close the gap, Harris will have to target the undecided, who represent about fifteen per cent of Latino voters, and will also have to appeal to at least some of the thirteen million Latinos who aren’t yet registered to vote. In the weeks ahead, either Harris will match Biden’s 2020 numbers, or the Republican Party will further cement its gains, Madrid noted, adding, “The latter would mean that there’s a new floor of support for Republicans—and it’s the mid- to high thirties, which is extraordinary.”