Artificial

intelligence has amazed people with its ability to create detailed images of

what you ask for in seconds.

The images can be colourful, decorative, and nice to look at.

People like

images created by artificial intelligence (AI), especially when they believe the

images were created by humans.

This is shown by Simone Grassini and Mika Koivisto in a new study published in Scientific Reports.

Some individual

characteristics were linked to a more positive view of AI-generated art.

Online survey

The researchers

selected 20 works created by artists in five genres, including Cubism and

Impressionism. The works were not well-known.

They then asked

the image generator Midjourney to create 20 images in the same genres.

About 200

people participated in an online survey. They were asked to rate how much they

liked the images.

Participants

also stated to what extent the images triggered positive emotions and whether

they believed the images were created by artificial intelligence or a human.

Participants also answered questionnaires that addressed their personality,

empathy, and attitudes toward technology.

AI image from the study.

(Image: Simone Grassini / Midjourney)

Fell for the AI images

It turned out

that people were not very good at assessing which images were made by

artificial intelligence and which were made by humans.

Participants

often believed that the AI images were created by humans and that the genuine artworks were made by AI.

People had a

clear tendency to prefer the AI images, and felt they gave them more positive feelings.

“I wouldn’t

take this result too seriously,” says Siomone Grassini, who conducted the study with

Koivisto.

Grassini is a

psychologist and researcher at the University of Bergen and the University of

Stavanger, and is interested in how people interact with artificial

intelligence.

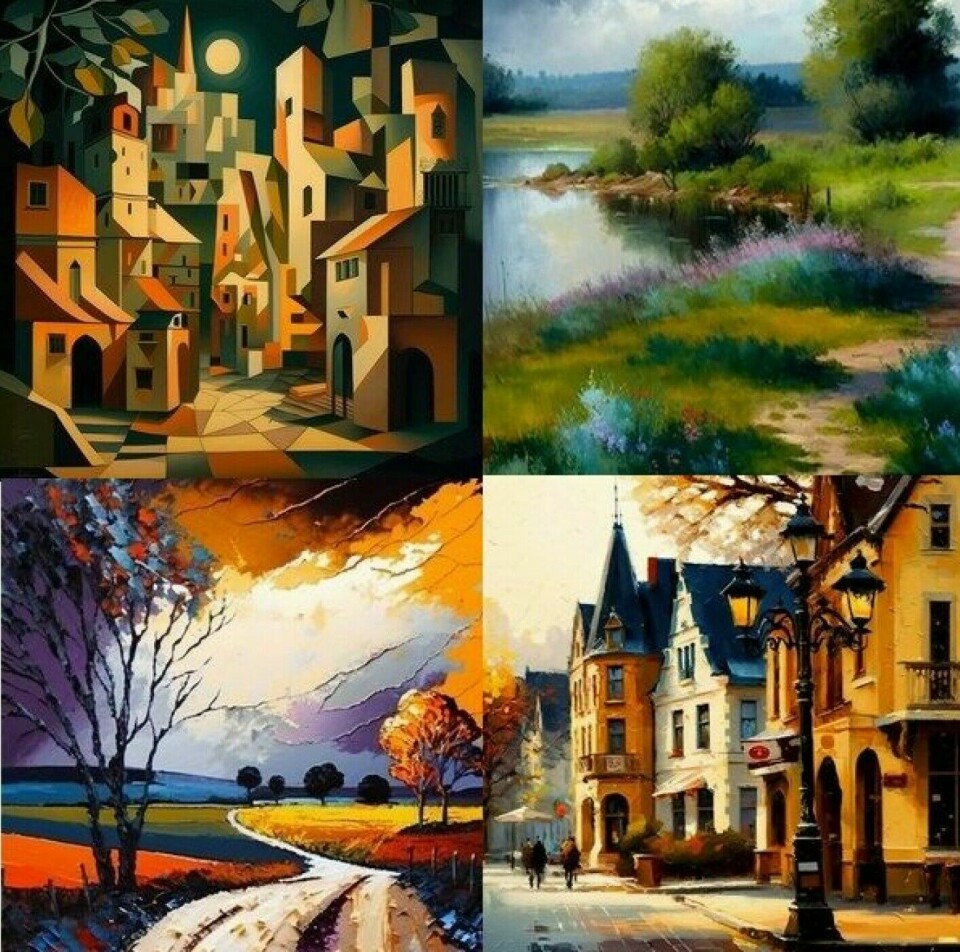

Examples of AI images that the participants saw in the study.

(Images: Simone Grassini / Midjourney)

Not a completely fair comparison

Grassini points

out that since the researchers themselves selected the artworks, they might have chosen less appealing works without meaning to.

Image noise was

added to the AI-generated images to make them more similar to the human artworks. This was done because the AI images had better resolution and were more colourful.

The images of

the genuine artworks were cropped to a square format and were thus not shown

as the artist had intended.

Simone Grassini is a psychologist and researcher at the University of Bergen and the University of Stavanger.

(Photo: Private)

One reason

people liked the AI images better might be that people think they recognise

them, according to Grassini. He has unpublished data suggesting this.

People believe they have seen AI images before to a greater extent than unknown, genuine artworks.

“It’s probably

because the AI images look like a lot of art that people see, since AI images

are based on art made by humans. The AI images are very average because they are the average of all art,” he says.

Images believed to be AI-generated were rated as uglier

The most

important result of the study is about something else.

Participants

gave poorer ratings to images they thought were created by artificial

intelligence.

“It seems that

where the image actually comes from doesn’t matter, rather what people believe

is what governs their feelings. The objective quality doesn’t seem to be that

important,” says Grassini.

“When participants

thought that an image was made by AI, it was regarded as uglier and of lower

emotional value, regardless of where it came from. When the image was assumed to be made by a human, it was considered more beautiful and as

having a higher emotional value.”

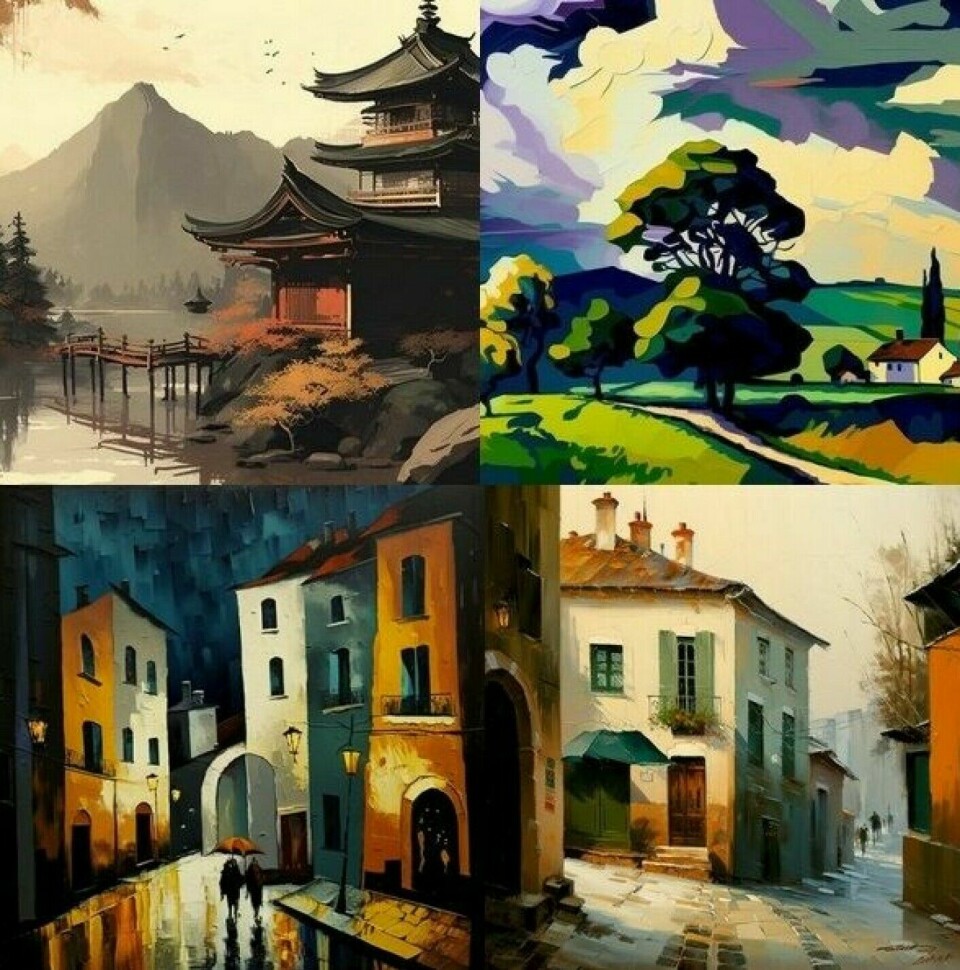

More examples of images created by artificial intelligence that were used in the study.

(Images: Simone Grassini / Midjourney)

People want a backstory

This study

finding does not surprise Alinta Krauth. She is an artist and senior lecturer

in digital culture at the University of Bergen.

“Many peoples

and cultures have a deep personal connection to art and see creativity as

something uniquely human,” she writes in an email to sciencenorway.no.

“Society wants to hold on to creativity as our special trait because it makes us feel different from other species. This makes us want to fight for it,” she writes.

Creativity is

often attributed to coming from an artist’s personal experience, she continues.

Alinta Krauth is an artist and senior lecturer in the Department of Linguistic, Literary and Aesthetic Studies at the University of Bergen.

(Photo: Alinta Krauth)

“People want

art to have a backstory – which can be more difficult to achieve if the

public believes that a work is entirely machine-made,” she writes.

Krauth points

out that being creative and making art that is well-liked can certainly

overlap, but they are not the same.

“Machines can

produce visual products that people find aesthetically pleasing without being

inherently creative,” she writes.

This is

especially the case when a machine is trained to follow the many rules humans

have established for what we find aesthetic, according to Krauth. AI can reproduce

genres, styles, or ideas. Therefore, the audience should not feel ashamed of liking an

image created by AI.

Personality traits played a role

The researchers

found two personal traits in particular that influenced participants’

impression of images they believed were generated by AI: A positive

attitude towards technology and being open to new experiences.

“The more positive attitude people had towards technology, the more beautiful they found the images they assumed were made by AI,” says Grassini.

But these

images were still less liked than images assumed to be made by humans.

“Another

predictive factor was the personality trait of openness to new experiences. We

found that people who are more open to new experiences tend to rate AI art more

favourably compared to people who scored low on this trait,” he says.

The researchers

had initially thought that this trait would yield the opposite finding. People

who score high on this personality trait are often also artistic, and the

researchers imagined that they might perceive AI art as a threat.

“But the

opposite turned out to be true. The explanation we give is that people who are

open to experience like to try new things. This is something new, so they like

it more than other people might,” says Grassini.

AI image used in the study.

(Image: Simone Grassini / Midjourney)

More and more alike

Grassini says

studying this topic is important because a lot of things will eventually be AI-generated.

“AI products

will become more and more similar to things made by humans. What we’re seeing now is that

it doesn’t really matter whether art is human or not, but whether it’s believed

to be made by a human or not,” he says.

“Customer

service created by AI might be perceived as worse, not because it’s objectively

worse, but just because it’s degraded as something created by AI.”

Grassini is

open to the possibility that these attitudes could change over time.

He does not

think that AI will be a threat to good artists, but that it could be more

difficult for people who are at a low level to break through.

AI can also be

used by artists, says Grassini. Maybe they’ll use it as inspiration. Or it

could become a trend to use AI images as a starting point and modify them, so

that they become more specific and connect more with people.

New genres and forms of expression

Krauth says

that the last thing she wants is a future where machines create poetry and

art while humans are left to do labour-intensive tasks.

“This is the

opposite of the utopia we were promised where AI would accommodate people and

give us time and space to be creative,” she writes.

But she does not believe this will be the future. She compares the fear of AI to when digital art

tools like Adobe and Macromedia came out.

“There was a

clear concern that digital art would replace traditional art forms. What we’ve

seen instead is that digital art has simply formed its own series of

interesting genres and that traditional art is still as widespread as ever,” she writes.

“Over time, I hope AI becomes a similar tool in the digital toolbox, by creating new artistic

genres, aesthetics, and forms of expression around it, while other genres and

tools remain as relevant as always.”

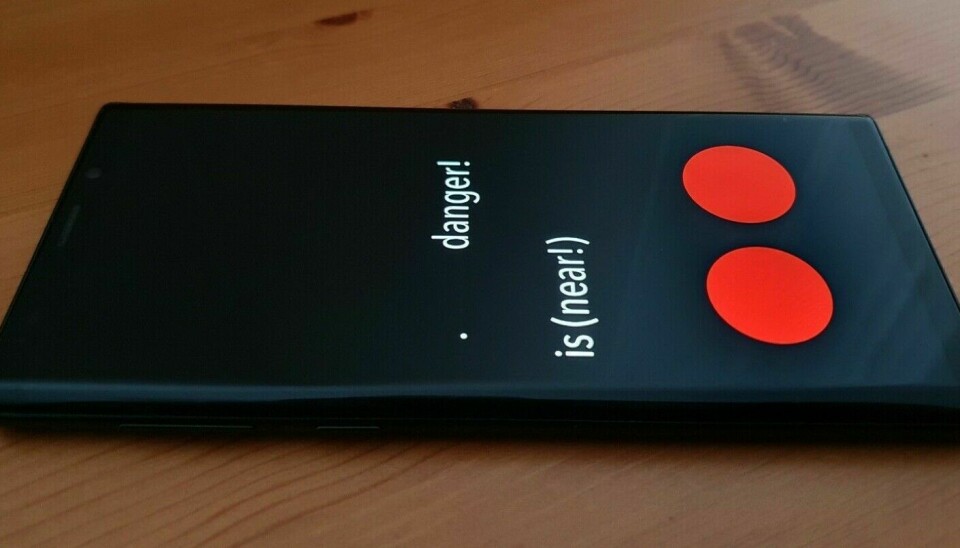

The (m)Otherhood of Meep, which is accessible through a smartphone, Alinta Krauth has used artificial intelligence to realise her idea.” alt=”” loading=”lazy” style=””/>

The (m)Otherhood of Meep, which is accessible through a smartphone, Alinta Krauth has used artificial intelligence to realise her idea.” alt=”” loading=”lazy” style=””/>

In her work The (m)Otherhood of Meep, which is accessible through a smartphone, Alinta Krauth has used artificial intelligence to realise her idea.

(Photo: Alinta Krauth)

Used AI in her own art

Krauth uses

digital tools in her art. Her works contain sound, animation, images, and

elements that the audience can interact with.

She reminds us

that artificial intelligence is much more than a handful of websites offering image generation.

“It’s this broader world of artificial intelligence that I think artists should look into and find interesting,” she writes.

Krauth has recently been in Spain and installed an exhibition with her colleague Jason Nelson,

where AI is an important part of the exhibition.

She has also

used AI in her work The (m)Otherhood of Meep, which is opened with a smartphone, and in which AI is trained to learn to recognise bat sounds.

“When the work

hears the correct vocalisation, content created by me appears on the screen. I think this

is a good example of how artists can integrate AI into their work in ways that

allow them to create the seemingly impossible, instead of replacing their own

role as artists,” Krauth writes.

Reference:

Grassini, S. & Koivisto, M. Understanding how personality traits, experiences,

and attitudes shape negative bias toward AI-generated artworks, Scientific

Reports, vol. 14, 2024. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-024-54294-4

———

Translated by Ingrid P. Nuse

Read the Norwegian version of this article on forskning.no