Arthur Hatt has just returned from school. It’s been a particularly fun day today as rehearsals are underway for his school play, Aladdin – and he has one of its most important parts, the Genie.

Although Arthur is back at school full time now, there have been long periods where he was only able to manage half days. “I’d go in for the morning and then come home and just go to bed and sleep or read in bed,” he says.

The reason is that Arthur has Crohn’s disease, a type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Now aged 11, he was diagnosed with the condition aged nine – but his mother Sian says that in hindsight, he was showing symptoms from a very early age.

“From the age of about 12 to 18 months, he was having problems with his tummy – loose stools all the time and lots of stomach pains,” she says.

Getting a diagnosis was not straightforward. There was no family history of inflammatory bowel disease or Crohn’s disease, so no one thought to consider this option. (Since then, however, Arthur’s older brother has also been diagnosed with the condition.)

“We were told he had toddler diarrhoea, which is common and he’d probably grow out of,” Sian says. “Then they said try eliminating dairy from his diet as it could be an intolerance. Then they said, oh, well, now try and eliminate gluten. When he was five or six, we got a referral to our local hospital who diagnosed him with abdominal migraines.”

Eventually, Arthur was seen by a doctor who recognised the signs of IBD and gave him a simple test known as a faecal calprotectin test, which looks for unusually high levels of the protein calprotectin in the stools – a sign of inflammation. By this time, he was experiencing a lot of pain, as well as blood in his stools.

Following the test, he was referred to Addenbrooke’s Hospital, where he was seen by Professor Matthias Zilbauer.

“That was the first time really that we felt like, OK, somebody knows what’s happening and there are things that they can do,” says Sian.

Arthur was prescribed the drug azathioprine, which he is still on to this day. Because it can take time for the effects of the medication to work, he was also temporarily prescribed steroids. “They made me feel jittery,” he says, “and I was really, really hungry.”

Azathioprine by itself has not been enough to fully control his symptoms, so he has had to try several other medications. He is also receiving infliximab, which is given via infusion at Addenbrooke’s.

“The first indications seem to be quite promising,” says Sian. “Even after the first dose, there seems to have been an improvement.”

The drugs do, however, come with side-effects. Azathioprine, for example, can make the skin more sensitive to light, so Arthur has to wear sunscreen whenever he goes outside. The treatments also tend to suppress the immune system, leaving him more susceptible to infections.

“Autumn has been tricky in the past, because it’s cough and cold and virus season at school,” Sian says, “Arthur tends to pick up every one of them, and it’s tiring for him when that happens.”

The family have learned to pace themselves, working out through trial and error how much Arthur is able to do without tiring himself out.

“School holidays now are a lot more about resting than they are about busy days,” Sian says. “We try and keep things quite chilled. He’s so good at pushing through and doing things. He likes to be a busy bee, but we found that if he pushes through too much, he can then cause himself more trouble in the long run.”

Fortunately, Arthur still manages to do the things he enjoys. He enjoys performing – hence his starring role in Aladdin. “I really like dancing, especially Latin and street dance,” he says. “I manage to do most of the things I like, but I get tired sometimes.”

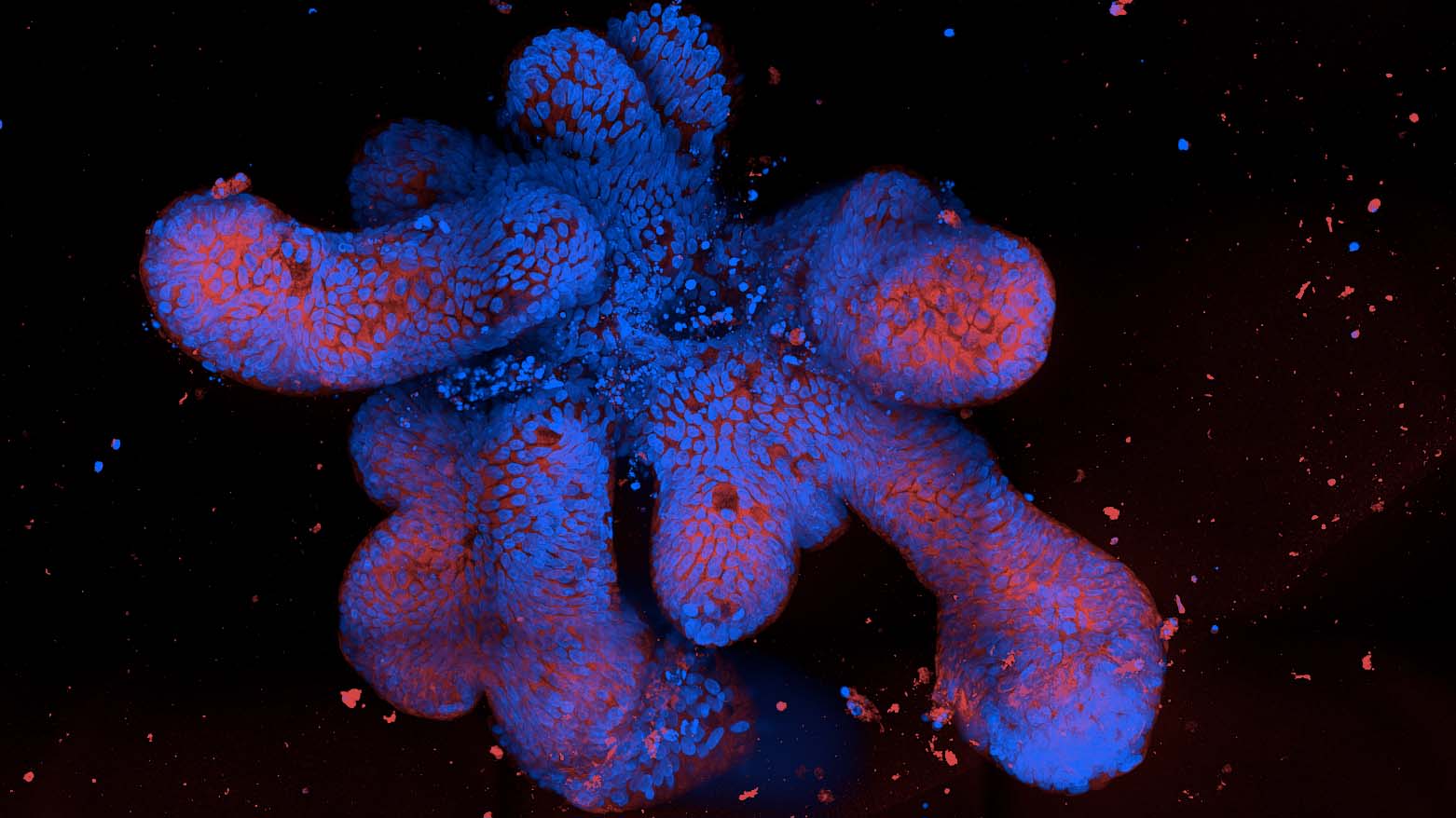

Arthur is one of the children taking part in the Translational Research in Intestinal Physiology and Pathology (TRIPP) study at the University of Cambridge, which is aimed at understanding our gut health. He has donated some of the cells from his intestine, which Professor Zilbauer are colleagues are now using to grow ‘mini-guts’ to better understand Crohn’s disease. Arthur and his family have met the scientists at a family day at the hospital aimed at showing the children how they’re helping research.

“I think it’s quite cool to be part of the study,” he says. “It’s nice to know they’re trying to get more information about Crohn’s.”

Sian adds: “The real hope is that eventually, we’ll be able to take away a lot of the trial and error with what works and what doesn’t work – because it’s different for every patient. That would be amazing.”

These days, more and more children are being diagnosed with Crohn’s disease and IBD. To these children, Arthur has a message:

“There are bad days and there are good days, but eventually you’ll find the right medicine. Sometimes it can take a really long time, but eventually they’ll find the thing that works for you.”

For now, though, he’s just looking forward to getting on stage and working his magic on the audience.