The rise of generative AI tools such as ChatGPT represents one of the most significant technological disruptions since the advent of the internet. Educators and administrators in higher education face complex ethical dilemmas that must be addressed, especially in how AI is integrated into teaching, research and learning.

At the core of these challenges is the concept of “interpretive flexibility”, a term borrowed from the social construction of technology (SCOT) theory. This refers to the idea that technology can have multiple meanings and uses, shaped by the different perspectives of its users.

For universities, this means that while some view AI as a powerful educational tool, allowing for more efficient work, others see it as a threat – particularly in terms of originality, academic integrity and ethics.

Ethics and risk in AI use

Considering the ethical dimensions of AI, the conversation inevitably turns to how this technology is shaping the future of work and learning in academia. AI’s capabilities – and its ever-evolving affordances – raise questions about what it means to contribute original thought.

At a time when universities are seeking to showcase their value and development of critical thinking and creativity, the use of AI can blur lines between individual effort and machine assistance.

For example, should students be required to disclose when they use AI to help with their coursework? Or does it constitute plagiarism if a student uses AI to write a paper or generate research results?

These are not hypothetical situations. In some instances, AI-generated work might even outshine what human students can actually achieve, challenging traditional views on academic merit.

Academics and administrators are beginning to recognise that ethical considerations go beyond just acknowledging the existence of AI.

Transparency, accountability and intellectual honesty are pivotal. Without clear guidelines, we risk falling into a grey zone where ethical standards are ambiguous, leaving room for misuse.

Psychological contracts and the role of ethics

Ethical behaviour in the workplace and academia often stems from unwritten social norms, a concept that can be understood through psychological contracts theory (PCT).

In the absence of explicit regulations, people rely on psychological contracts – unspoken, and often personal, agreements about what is deemed acceptable or ethical behaviour.

Psychological contracts guide individuals to behave as influenced by their culture, upbringing, moral values, education, conscientiousness and various other factors. This framework is particularly useful in understanding how academics and students can approach the use of AI when formal policies are lacking.

For example, some students may perceive AI tools as acceptable work supplements, similar to hiring a tutor or using a spellchecker. Others may view them as a breach of academic integrity, especially when originality is highly prized.

Similarly, faculty members can face dilemmas when using AI to assist with research. While it can help to analyse data faster, does it undermine the integrity of their research if the bulk of this work is outsourced to a machine?

These questions show that AI, much like earlier technological advancements, is in a phase of interpretive flexibility. Its role and ethics are still being debated, and closure – where a consensus on its use is achieved – remains elusive.

The role of universities in shaping AI use

Given this interpretive flexibility, universities have a crucial role to play in shaping the future of AI use in academia, and several steps can be taken to navigate the ethical complexities surrounding generative AI:

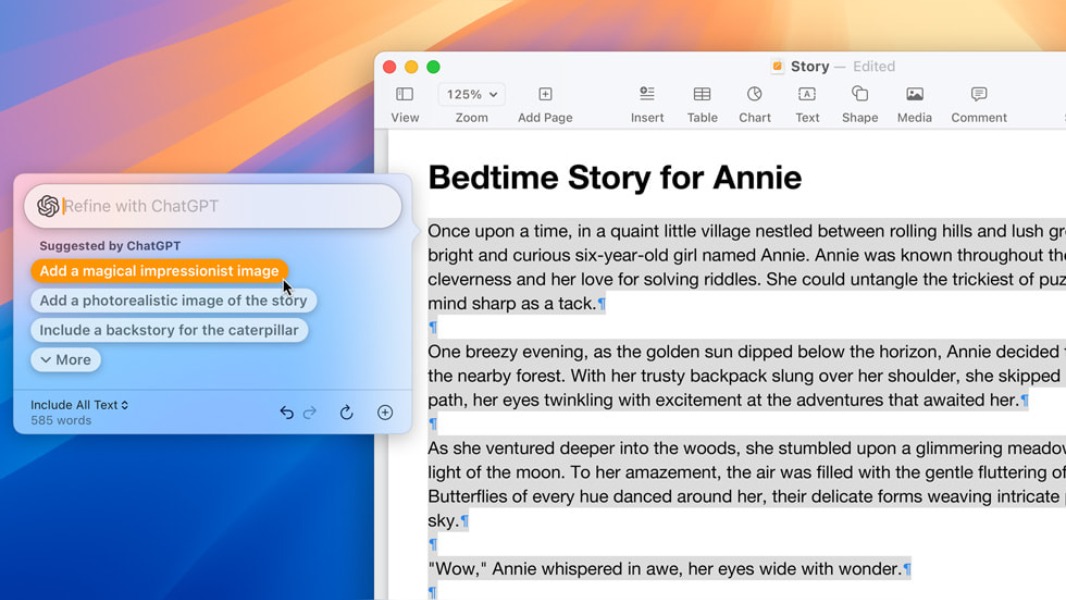

Establish clear guidelines: Universities should define when and how AI tools can be used, for both students and faculty. Transparent policies that specify acceptable AI usage in research, coursework and administrative work can help reduce ambiguity.

Foster ethical awareness: Incorporating discussions about the ethical implications of AI into curricula helps students and faculty to understand the moral consequences of relying on these tools. This can also include a focus on data privacy, accountability and the risks of AI-generated misinformation.

Emphasise originality and intellectual honesty: AI can help with many tasks, but universities must reinforce the value of original thought and critical analysis. Faculty should encourage students to use AI as a supplementary tool only, rather than a replacement for individual effort.

Develop AI literacy: Just as students learn to evaluate the reliability of information sources, they should also be taught to critically assess outputs generated by AI. AI is not infallible – its outputs can be biased, inaccurate or even misleading. Educators should train students to question AI-generated content critically.

Monitor the evolving role of AI: AI technologies are continuously evolving, as should policies surrounding their use. Universities need to be agile, revisiting their guidelines as new capabilities and ethical challenges emerge.

A new ethical frontier

AI presents both opportunities and challenges for higher education. As the technology becomes increasingly integrated into academic life, it is essential that universities strike a balance between embracing innovation and maintaining integrity.

The interpretive flexibility of generative AI demands that educators, students and administrators work together to develop clear guidelines that promote responsible use.

Based on my own psychological contract, I avoid using AI assistance for writing – be it in emails, academic manuscripts, practitioner reports or even this article – in favour of using my own voice.

However, I have implemented AI-trained tools to help faculty search and navigate policy documents on the school’s intranet, and I also use AI to derive new analytical insights on data gathered for assessments and quality assurance.

Ultimately, the ethical use of AI in academia is not just a technical issue but a social one. The choices we make now will shape the role of AI in education for generations to come. Universities must take a proactive stance, guiding this transformation responsibly and ethically.

Lakshmi Goel is dean of the School of Business Administration at Al Akhawayn University.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.