In the late 1990s and early 2000s, “Nigerian Prince” emails became infamous — typically involving someone claiming to be royalty and asking for money that they promised would be paid back with a hefty commission added once the purported royal offspring came into his inheritance.

Most people know by now that these outlandish claims are a scam. But as internet connectivity became cheaper and more accessible on the African continent, those scams have morphed into something far more sophisticated, and much harder to recognize.

I have traveled with a CBS News team to Ghana fairly often, and every time we’ve visited, we’d hear about so-called romance scams. For more than a year, CBS News has been investigating the devastating toll that overseas-based scams are taking on Americans of all ages and background. The amount of money flowing from American victims to fraud syndicates has topped $10 billion, according to the Federal Trade Commission. And that number, experts say, is almost certainly an undercount.

Over that period, CBS News has tried to understand what — and who — is driving the criminal activity, but scammers have been unwilling to talk. Why would any fraudster willingly share the tricks of their trade, after all?

And make no mistake — while many young Ghanaians are lured into potentially lucrative lives of cyber fraud, they quickly become tools of transnational criminal syndicates that work in what’s become a billion-dollar industry. But earlier this year, the CBS News team began to peel back the veil of secrecy on one of the criminal enterprises targeting unsuspecting Americans in the perceived safety of their own homes.

Ghana’s underground “boiler rooms”

A CBS News South African photographer went undercover to film inside a so-called “boiler room” in a dusty part of Ghana’s capital Accra, where young men work for a syndicate boss who provides them with laptops, phones, internet and stable electricity. They work late into the night, trawling online dating sites for lonely, older victims they cynically refer to as “clients.”

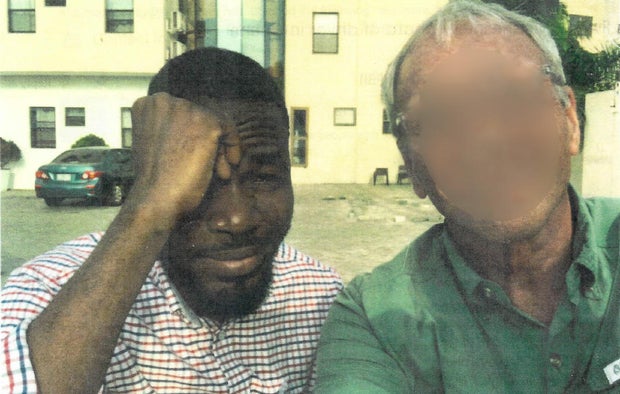

Eventually we convinced a junior member of one of the operations to talk to us on the condition we hid his identity. He claimed he didn’t do it much anymore, although the evidence we saw suggested it was pretty much his full-time job.

In order to persuade him to speak to us, we agreed to conceal his identity, referring to him only as Abdullah. He has a wife and kids who know nothing about his double life. His boss gets 60% of the cut and Abdullah takes home the remaining 40%.

He told us he mainly targets American men, as they’re easier to trick. Women, he said, take a lot longer to fall in love.

He poses as a beautiful woman living in the U.S. His victims on the other end of the dating apps, on the other side of the world, have no idea they’re actually talking to a young man in Ghana.

“I pretended to be a girl,” Abdullah said. He builds trust by sending “flowers and chocolate” after convincing his victims to provide an address.

“If you chat like you are in Ghana, they know that Ghana and Nigeria (have) plenty of scams,” Abdullah said, explaining that his work requires a fair amount of time spent researching his purported home state: “You have to study, you have to know a lot about it. If you’re, like, in California, we have to set our time and everything… California time.”

Abdullah and those like him in the boiler rooms are fairly low down in the criminal hierarchy. Most syndicates have “closers” who step in once a victim is on the hook.

The closers

The closers are often well-educated young men who speak English well. At first they were skittish and reluctant to talk.

But we got the sense they were proud of their work, and wanted to show it off.

The two men who finally agreed to speak to CBS News — a syndicate boss who called himself Voodu and senior operator who went by Cola (not their real names) — said they only agreed to talk because their “motives are misunderstood.” And once they started talking, they couldn’t stop. (Although they were accompanied by an “enforcer” who glared at us throughout the interview and threatened that his, “boys will hunt you down,” if we revealed their identities.)

Voodu said he has been in the game for nearly 15 years, and he claims to employ around 50 people.

“I’m the mastermind behind the whole thing,” boasted the smooth-talking operator, oozing confidence. He even tried to charm us, styling himself as some kind of Robin Hood.

“Where I come from, it’s very hard. It’s very difficult for people to get money,” he told us. “So I came up with this whole idea just to support my neighbors, those who do not have it, the poor, the needy, the orphanage… just help everybody out.”

We have no idea if Voodu has actually tried to help his community, but he’s certainly living the good life. He claimed he would leave the world of crime once he’s made enough money to start his own business.

He acknowledged that his work in the meantime does harm many other people, and said, “sometimes, I feel bad.”

But not bad enough to stop doing it.

Cola said he’s a university graduate who didn’t have enough money to pay his school fees, and then after he’d qualified as a teacher, couldn’t find a job. We asked him how he felt about making a living by stealing money from others.

“It has both sides. It’s a mixed feeling,” he said. “Sometimes I feel disappointed, like I didn’t go to school to do this. I can do better than this. … Sometimes when I take money from people and feel like, ‘Oh my God, these people, how are they going to feel?’ l imagine that it is my dad. But you know, there’s no sympathy, because once you go on the sympathetic side, you go hungry.”

CBS News

“If you have the conscience, you can’t proceed, you can’t push. Because sometimes I need to push people to the limit to get something from them,” he said, adding that for many young men in his position, “if this game had not come, they’d have to pull the trigger on people and steal from them.”

The big con

They may not be putting a gun to people’s heads, but their criminal actions are still devastating for victims left broken-hearted and financially ruined.

“I fish everywhere in the world,” Voodu told us, but he said the easiest victims to catch, “they are Americans.”

He said his team in the boiler room begins by sending a victim little tokens of affection; chocolates, a teddy bear, even ordering their favorite food online and having it delivered to their doorstep. They shower them with attention, messaging them constantly and making them feel loved, adored and special.

“I will make you fall in love with me,” he boasted. “If you don’t hear from me within a second, you know, you wouldn’t be happy, you’d be worried.”

When a victim insists on a video call, Voodu said he hires online porn actors and records them acting out scenarios he directs — from the mundane to the more raunchy.

“They think they’re talking to this beautiful blonde woman (that) I have paid to just have her on video call,” he tells us. If a victim gets suspicious, Voodu is ready. He showed CBS News how he uses an image of one of his recruited porn actors to forge an image of an American passport as proof of identity.

If the victim demands an in-person visit, they arrange for a meetup with a woman who gets a cut of the profits.

Building trust can take months.

“We do all that to get his attention and trust,” he explained. “Then, boom — we chip in business.”

Then it’s time for the big con: Getting their victim to part with huge sums of money.

The set-up often centers around Ghana’s globally renowned goldmines, the largest in Africa. The scammer, still posing as the woman the victim has come to trust, will claim to be in line to inherit one of these mines. The victim is invited to invest in the mine with the promise of huge returns that will ensure a wonderful future for the happy couple.

They show forged ownership documents, complete with official looking seals.

The pair claimed to CBS News that their biggest payout was in the millions.

One victim’s story

Gerald Kpangkpari heads up the anti-money-laundering unit in Ghana’s Economic and Organized Crime Office.

“We have a lot of unemployed youths, people who are talented, who have gone to school, and they don’t have anything to do,” he explained. He described their main targets: “Male. Caucasian male. … They are elderly people who are quite lonely.

The Ghanaian scammers we have spoken with told us they prefer targeting men as they’re easier to trap and less likely to report it, because of their shame over being conned.

Among the victims is a 75-year-old American radiologist who we’re identifying only as John. He declined to give an interview for precisely that reason — he’s ashamed of having fallen into the trap.

John’s daughter went to FBI agents, who handed the file over to Ghana’s organized crime unit.

Kpangkpari told us that John believed he was in love with an Australian woman named Grace Erskine who lived in the U.S. He was actually talking to 34-year-old syndicate boss Alfred Kwame Ayivor, posing as Grace.

Ayivor controlled the entire scam, which included the extreme measure of hiring a woman to play the part of Grace for any in-person meetings John insisted on. Below is part of a text message exchange between Ayivor and the woman he hired:

Woman: What’s my cut?

Ayivor: How about $100,000?

Woman: $250 000. Without me, everyone gets nothing. I could always call him [John] and say it was a scam.

She clearly did not follow up on the threat. Pretending to be Grace, she visited John in the U.S., even meeting his family, Kpangkpari told us.

She claimed she’d inherited a Ghanaian gold mine, which John was offered a stake in to secure their future together. To seal the deal, the couple were to meet again, in Ghana’s capital city, as organized by Ayivor:

Ayivor: That’s where we stand with John, one week in Ghana with Grace.

Woman: Yuck. He’s so gross.

Ayivor: One week + TLC

Woman: I am not opening my legs for him.

John did travel to Ghana and stayed for some of the time at the same hotel as Grace in Accra. Ayivor posed as their driver the entire time, apparently to keep an eye on an operation he hoped would yield a big payday.

By the time the fraudulent romance was over, Kpangkpari said John had shelled out more than $700,000 on what turned out to be a non-existent investment in a non-existent gold mine.

Kpangkpari said the “exchange of information” between his team and U.S. law enforcement agencies is always crucial, but it was the sheer quantity of money flowing into Ayivor’s account that raised a red flag for the Ghanaian detectives, as Ayivor was officially unemployed at the time.

“We realized that the person did not have any form of work that is commensurate with the amount of moneys that were coming into his account,” Kpangkpari told CBS News.

Ayivor was arrested in 2019 and his assets were seized, but he died of an unknown illness before facing trial. Kpangkpari’s unit has been able to return a little over $36,000 to John, and they’re still trying to recover more of the money the American sent to Ghana.

As for the mysterious blonde woman who posed as Grace — she had vanished after her contacts with John. The Ghanaian authorities identified her as an Australian national named Rebecca Jade Silk.

The CBS News team tracked her down in September outside Sydney, Australia. When confronted, she kept her mouth shut and her head down, refusing to confirm or deny the allegations. Silk has not been charged with any crimes. She remains a person of interest for the Ghanaian authorities.

No turning back from the life of bling

The “Yahoo boys” of the boiler rooms and their so-called hustle kingdoms have been glamorized in popular West African culture, perhaps unsurprising given the millions they claim to be raking in.

When asked if their victims go into debt because of what they do, Voodu laughed and said, “yeah.”

They live a flashy lifestyle — complete with expensive clubs, beach parties and fancy cars. We filmed one group celebrating a big payout by just throwing money in the air.

Given that they lie and cheat for a living, I put it to the group bluntly: How I could be sure they weren’t lying to us in the interview?

Cola responded with annoyance: “I don’t lie and cheat for a living. I’m using what I have here [pointing to his head] to survive. I decided to be honest to you.”

In a country where poverty is rife and jobs are scarce, there’s a long line of kids ripe for recruitment into a life of crime. Once they’ve tasted the good life, they seldom turn back — regardless of the cost to victims an ocean away.

CBS News investigative producer Andrew Bast contributed to this report.

Investigating Online Scams

More

More

Debora Patta