Investors have poured tens of billions of dollars into startups and publicly traded companies to profit from the third major technology cycle of the past five decades.

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

In the last eighteen months, there is a good chance that you have heard enough and more about how the revolution of artificial intelligence (AI) could add $15 trillion to the global GDP and magically transform our lives. The world’s tech giants are in an arms race to dominate in the new era.

“AI will, probably, most likely, lead to the end of the world, but in the meantime, there’ll be great companies,” Sam Altman, co-founder and CEO, OpenAI, declared in June 2015.

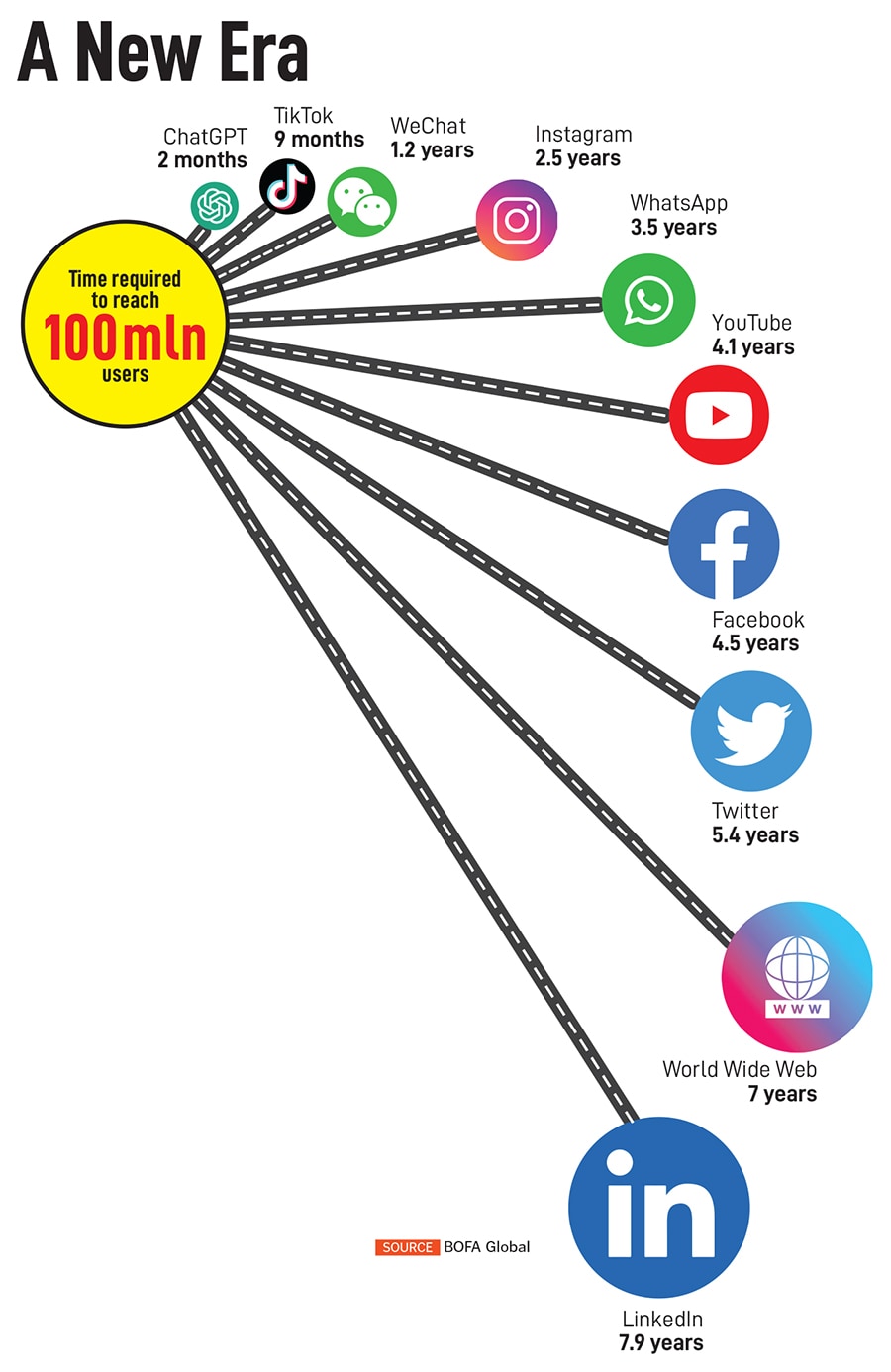

Altman’s OpenAI is the poster child of generative AI (GenAI), a generation defining technology wave, which began nearly two years ago with the launch of ChatGPT. Its meteoric rise sparked hype and fear like no other technology has in recent times; goading Big Tech to spend billions on data centres and computing hardware to building AI infrastructure.

“GenAI already has the intelligence of a college student, but it will likely put a polymath in every pocket within a few years,” notes Bank of America’s Managing Director Alkesh Shah.

Since its inception nine years ago, OpenAI, a Microsoft-backed AI research organisation that employs 1,500 people, has raised over $11.3 billion and was valued at around $80 billion in February this year. It is in talks, reportedly, to raise a fresh round of funds at a valuation of $150 billion.

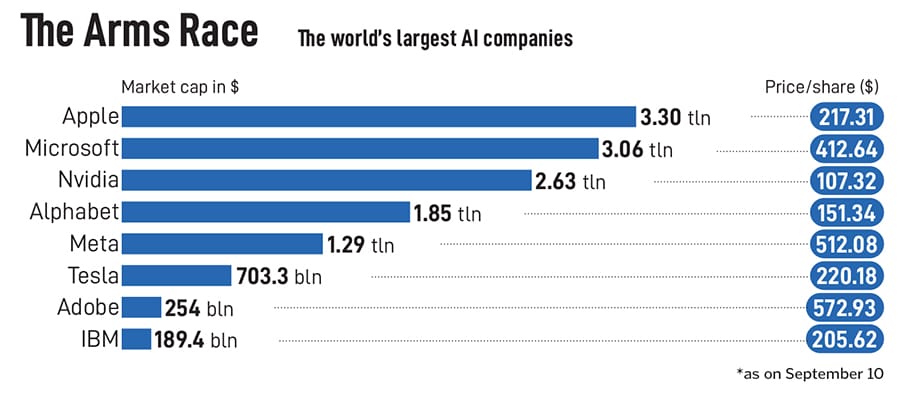

Inevitably, investors have poured tens of billions of dollars into startups and publicly traded companies to profit from the third major technology cycle of the past five decades. So much so that most businesses that are involved in AI saw a dramatic rise in their stock price over the past year.

Consider the case of one of the biggest winners, Nvidia. In June, the chip vendor crossed the $3 trillion mark to become the most valued company listed in the US. The shares of the ‘magnificent seven’ group of US tech behemoths also touched stratospheric levels. However, the yearlong euphoria on Wall Street ended last month as Nvidia stocks collapsed. In a matter of days, stocks of major tech companies crumbled and over $1 trillion was wiped off in the rout.

Consider the case of one of the biggest winners, Nvidia. In June, the chip vendor crossed the $3 trillion mark to become the most valued company listed in the US. The shares of the ‘magnificent seven’ group of US tech behemoths also touched stratospheric levels. However, the yearlong euphoria on Wall Street ended last month as Nvidia stocks collapsed. In a matter of days, stocks of major tech companies crumbled and over $1 trillion was wiped off in the rout.

“The problem is that Nvidia’s performance over the last three quarters, in particular, have created expectations that no company can meet,” explains Aswath Damodaran, finance professor, NYU Stern School of Business. “There are clear signs of more slowing to come, as scaling will continue to push revenue growth down, and operating margins will decrease as competition increases.”

Some of the speculative frenzy has given way to concerns if companies can materially monetise the massive investments on AI infrastructure build-out. Recent lacklustre earnings reports from tech leaders such as Meta, Microsoft, and Google, for example, have added to investor woes.

“GenAI is a revolutionary technology but it’s losing its shine because now investors are questioning its viability,” says Arup Roy, VP distinguished analyst, Gartner Fellow.

The Big Gap

AI capex is likely to touch $1 trillion in the coming months. Transformative business and consumer applications require powerful operating systems and accelerator technologies as the foundational components of hardware to train large language models (LLMs). This explains why the tech giants are aggressively investing in data centres and graphic processing units (GPUs). The challenge, however, is those companies have little to show to justify the staggering pile of cash deployed towards AI so far.

This shows a big gap in the ecosystem’s end-user value as companies struggle to report revenue growth from AI. David Cahn, partner, Sequoia Capital, argues that AI companies need annual revenues to the tune of $600 billion to pay for their AI infrastructure.

According to an analysis by The Information, OpenAI spends roughly $700,000 per day to run ChatGPT and is on course to post a $5 billion loss. Of its 350,000 servers, about 290,000 are dedicated to ChatGPT, suggesting the company’s hardware is operating at close to full capacity. Evidently, one of the fastest growing businesses is also perhaps the costliest to run.

Potential disruptions from regulators and lawmakers to govern data collection for reasons of privacy, safety, and ethics, could derail growth plans. Plus, unlike capex on building physical infrastructure, there is much less pricing power in the case of GPU data centres as new players building AI dedicated clouds continue to enter the market.

“If my forecast comes to bear, it will cause harm primarily to investors,” Cahn cautions. “Founders and company builders will continue to build in AI—and they will be more likely to succeed, because they will benefit both from lower costs and from learnings accrued during this period of experimentation.”

Most Big Tech players have signalled plans to increase spending as they strategically lay the groundwork for what they believe is a future led and powered by AI: Microsoft said its capex will be higher than last year’s $56 billion; Meta raised its full year capex guidance by $2 billion and it expects it to be between $37 billion and $40 billion; Google estimates its capex spending to be at or above $12 billion for each quarter this year.

Also read: Lightspeed India is leading the way in AI, EV and climate-tech investments. Here’s why

“The risk of under-investing is dramatically greater than the risk of over-investing for us here… Not investing to be at the front here has much more significant downside,” Sundar Pichai, Alphabet CEO, stated in the earnings call last month. Google’s second quarter capex accounted for roughly 17 percent of its total sales.

While acknowledging that there is a possibility that companies are over-building, Meta founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg reasoned that this is a rational decision. “The downside of being behind is that you’re out of position for the most important technology for the next 10 to 15 years,” he told analysts in July.

Blume Ventures’ Managing Partner Sanjay Nath has a ringside view of how Silicon Valley is riding the AI-wave. The San Francisco-based investor believes that a ‘one size fits all’ approach can’t work in AI and companies must pick the best model for the use-case at hand.

“The larger technology incumbents have been investing fairly rapidly and at scale on training models given that every new model renders the previous generation near-obsolete. The race there is certainly to be the latest and greatest at any given point of time,” Nath elaborates. “The future will likely have multiple high-quality models each with their own strengths.”

The Silver Bullet

Bank of America says the AI hype cycle has reached the ‘trough of disillusionment’ as investors tend to overestimate the magnitude of tech disruptions in the near term and underestimate it over the long term. Its team of analysts expects relatively short time gaps between AI infrastructure investment and monetisation due to the powerful foundation model operating systems that are in place.

“We caution investors not to discount GenAI’s cost savings and revenue-generating potential before usage even begins,” Shah highlights.

Industry leaders rule out immediate top and bottom-line growth though they are certain that the newest foundation models and GenAI apps will drive operational efficiency and productivity gains to lift the economy.

“We see many examples of real enterprises buying AI-first workflow products,” Nath says. “There is definitely a massive reality to the AI adoption wave.”

Microsoft’s Chief Financial Officer Amy Hood recently assured investors that its data centre investments will enable monetisation of its AI technology over the next 15 years and beyond.

Susan Li, chief financial officer, Meta, pacified investors that returns from GenAI may come over a long period of time. “We don’t expect our GenAI products to be a meaningful driver of revenue in 2024,” Li informed analysts. “But we do expect that they are going to open up new revenue opportunities over time that will enable us to generate a solid return on our investment.”

This is a sugarcoated pill for investors of publicly traded companies because they expect returns in a shorter time frame in comparison to, say, VC investors who are likely to have a longer time horizon of around 10-15 years.

Yet most agree that the current pace of capital expenditure on AI is not sustainable and one or more of the tech leaders may be forced to pull back on investments by early next year to allow revenue growth to catch up.

Dotcom 2.0?

The latest meltdown in tech stocks notwithstanding, experts brush off any comparisons between the current AI boom and the dotcom bubble of the late-90s.

“AI will be much bigger and transformative than the dotcom revolution or any other technological revolution we have seen,” asserts Srikanth Velamakanni, co-founder, group CEO and executive vice chairman, Fractal.

While both the cycles marked valuations of tech companies reaching unrealistic levels on the back of hope and excitement rather than a clearly defined profitable revenue stream, there are big differences too.

Most important, present day tech leaders are highly profitable and have proven business models that will not fail even if their AI plans bite the dust. They have strong competitive advantages in the form of proprietary data and a large user base.

“The dotcom companies didn’t have the kind of cash flow and demand visibility that the top US tech companies have today,” Siddharth Srivastava, head- ETF products and fund manager, Mirae AMC, points out. “US tech stocks are due for some correction but the AI theme will remain strong in the coming 3-5 years.”

JP Morgan research shows that the average PE ratio of today’s tech giants is around 34, which isn’t alarmingly high for growth stocks. Conversely, the average PE ratio of the group of listed dotcom companies was 59.

However, there is growing concern that the valuation of some AI startups might be nearing bubble territory as opportunistic players jump onto the bandwagon.

“There are some startups that have .ai affixed to their company names but aren’t able to design more than AI ‘wrappers’,” Nath says. “We worry this category of startups may be successful at raising money initially but will soon flail, and ultimately fail.”

The Indian scene

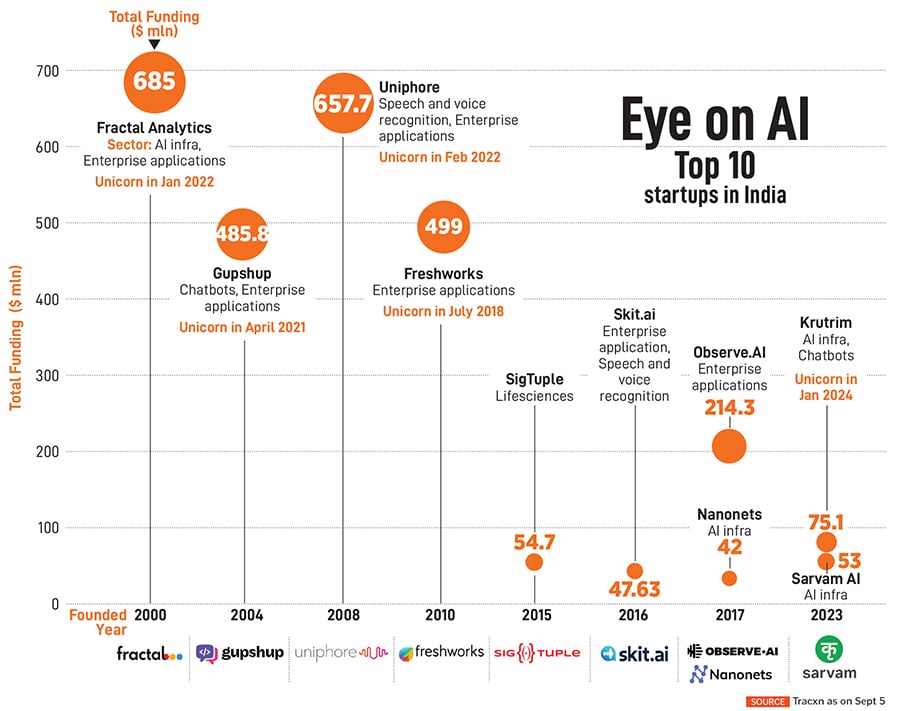

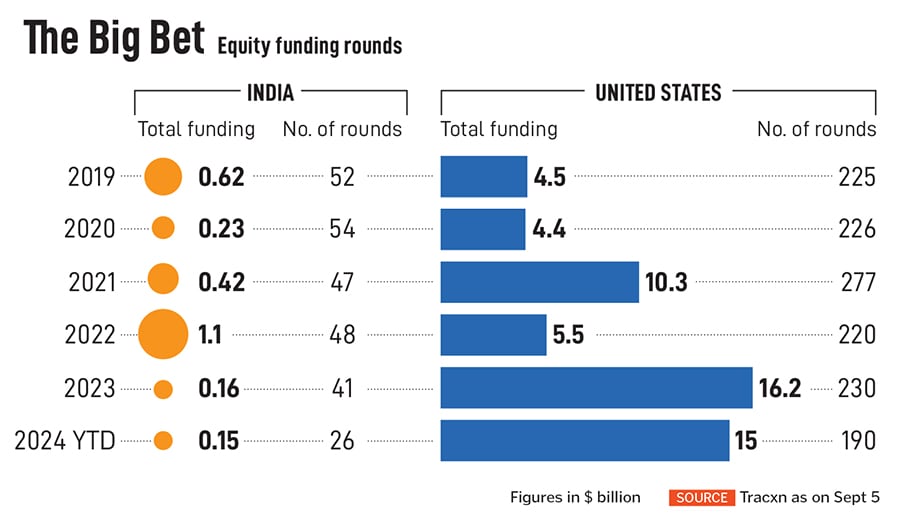

The AI landscape in India is relatively less crowded. Since 2009, investors have pumped in $2.6 billion into domestic startups building AI for various applications. This is a miniscule fraction of the $55.8 billion that flowed into AI startups in the US during the same period.

The debut of ChatGPT in November 2022 made entrepreneurs realise how the real power of AI can be made accessible to millions of users worldwide.

Roy says he is slightly disappointed with homebred tech providers. “Most of these companies are followers and there isn’t much innovation yet,” he complains. “Investors want to see ‘proof of value’ and are no longer simply convinced with a ‘proof of concept.’”

The veteran research analyst, however, is excited about the progress of domestic companies in leveraging conversational AI to, for instance, guide a customer’s buying journey. He is also hopeful that more ‘pick and shovel’ beneficiaries will emerge. “This is extremely rich in terms of opportunities,” he opines.

Building cash-guzzling foundational models from the ground up for artificial general intelligence (AGI) applications calls for billions of dollars of investments. “There’s no chance of any Indian company getting funded at that level,” Velamakanni rues. “You need vision combined with capital and talent.”

But Velamakanni believes that India can leverage foundational models to build application-oriented companies, that can solve real-world problems across various sectors, without billions of dollars in funding. “India is very competitive in this space and such startups are being able to raise funds,” Fractal’s co-founder says.

Fractal has raised $685 million from 13 investors since it was founded 20 years ago. It joined the club of unicorns in January 2022, when it raised $360 million from TPG at a revenue multiple of 7.1 times and a post money valuation of $1 billion.

In the age of AI, Nath advises founders across the ecosystem to think about the go-to-market (GTM) strategy very differently. “The sequential approach that worked in the past for SaaS might not work anymore. The path to a 100M ARR business looks to be more accelerated with AI, which means that the GTM strategy and channels to get there will also need to evolve,” he elaborates.

Historically, most disruptive technologies have reached a stage of adoption after 15-30 years. The radio, for example, was invented in 1890, but it wasn’t commercially available until 1920. Likewise, the television was developed in the 1920s but was found in homes only in the 1950s. Similarly, email, though invented in 1969, was in vogue only in 1997.

Predicting the future is a fools’ errand, but if the protagonists are to be believed, GenAI is likely to be mainstream in the coming three to five years, which could perhaps richly reward companies betting on it. The jury is out on its end-use though. Time will tell us how ‘real’ artificial intelligence is.

]]>

(This story appears in the 04 October, 2024 issue

of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, click here.)