Rodan & Fields is the latest multi-level marketing company to pivot to an affiliate marketing business model. As of Sept. 1, Rodan & Fields sellers will only be able to make money based on commissions of the products they sell. If you read that and thought, Huh, isn’t that how business generally works? you would be right.

The change is a catastrophic one for a lot of current MLM top sellers, though, and also betrays the ghoulish truth at the center of these companies: When a company with a famously exploitative business model pivots to mimic the influencer economy, it’s not an ethical choice, but a way to adopt the latest vernacular of the unachievable entrepreneurial dream to sell their mediocre products.

MLMs, also known as direct marketing, network marketing, or pyramid selling, are businesses that sell products, but that are built primarily on the recruitment and retention of independent sales associates and the commissions on their sales.

“So say I was like, ‘Hey, join me in business.’ You bought a business kit,” said Emily Lynn Paulson, a former R&F seller and the author of Hey, Hun: Sales, Sisterhood, Supremacy, and the Other Lies Behind Multilevel Marketing. “I would make money off of that, plus anything you sold, plus anything you bought, and then any customers you have, plus any team members you bring on and so on and so on and so on, and that’s the pyramid.” When you join an MLM, you buy your products from the person who recruited you, your “upline,” and if you recruit people, they buy their products from you. They’re your “downline.” The more people join the business, the more it starts to look a bit like a … pyramid. Pyramid schemes are illegal, but MLMs are not, because there is a product or service involved in the business.

Paulson says millions of Americans are members of MLMs like R&F, Amway, Mary Kay, or Herbalife. People who work with—with, not for—these organizations are neither W-2 employees nor true independent business owners, but rather something in between, beholden to the larger company’s policies and products but without both the safety net, insurance, and protections employees are entitled to or the autonomy of business owners. Most importantly, when the MLM changes its business model, the sellers are vulnerable to the consequences.

R&F announced its pivot a couple weeks ago in a press release, and MLM sellers have been reeling. You might know Katie Rodan and Kathy A. Fields as the duo responsible for Proactiv, the sexiest acne treatment money could buy from the TV in the early 2000s. Since 2007, the pair have run Rodan & Fields, an MLM that sells skincare, yes, but more importantly sells the promise of financial independence, community, and confidence to its more than 400,000 “independent skincare consultants” looking to build their own businesses.

According to Paulson’s book, the vast majority of people who buy into MLMs lose money. But that’s a truth often left out of the pitch sellers use to attract new clients and “team members.”

MLMs have always preyed on marginalized groups with their rhetoric about making easy money from home in a flexible situation; the first Tupperware party was held in the 1940s by Brownie Wise, who recognized the power of marketing specifically to the women in her community. Today, they reel in their marks using feminism-adjacent language about being your own boss, running your own business, and retiring your husband (Paulson says at least 80 percent of MLM sellers are women).

These businesses gained new traction in the last decade in part because of how effectively they piggybacked off the girlboss feminism of the 2010s, but reporting on the industry has shifted public opinion on them. In part because of documentaries like LuLaRich, podcasts like The Dream, and Paulson’s book, the average consumer is more savvy of the risks involved with joining an MLM. The stereotypical “hey hun” message is suspect because it’s been parodied so often and so effectively. The illusion doesn’t work anymore, so it’s hard to take sellers’ messages about financial independence and community seriously.

MLMs know this, and they’re adjusting accordingly. R&F isn’t the only MLM to pivot away from this model. Beauty brands Seint and Beauty Counter and wellness company AdvoCare have also ditched the MLM model, either by choice or because they were forced to do so by the FTC.

Affiliated with R&F or not, MLM sellers have started to make statements about the changes. Amber Olson Rourke, whose TikTok bio says she is “president of Neora,” another MLM company, had a “big problem” with the decision. “So these people have put their blood, sweat, and tears into building this brand, into mentoring and training people with no sales experience how to represent their brand, putting their own reputation, their own name behind the company, and then one day they woke up and the company’s like ‘Peace,’” she said in a TikTok.

Another R&F seller with the username @bethtag76 posted a video statement to Instagram in which she said, “I’m sad for my friends who have built multimillion-dollar businesses, to have that just ripped away from them.”

By switching to an affiliate marketing model, R&F is adopting an economic model legible to most internet users. People make money in affiliate marketing when they post about products online and direct their audiences to purchase. If an influencer is part of an affiliate program, they get a unique URL for product to share. When a user clicks that link, it attaches a cookie to their device; if the user makes a purchase within a certain time frame, the influencer gets a small referral commission.

Affiliate marketing is a hallmark of the influencer era, and a huge revenue driver for people who monetize their lifestyles online, from Stanley cups and glass straws to mechanical keyboards and gaming headsets. This isn’t exclusive to influencers, either; product recommendation sites like Wirecutter and The Strategist use affiliate links to generate revenue, and Defector even has a Bookshop list of affiliate links.

You used to have to have a huge, trusting audience to be able to make significant money from affiliate marketing. But with its introduction of TikTok Shop, the platform makes it alarmingly easy to buy products without ever leaving the app, and now non-influencers can make bank off affiliate links. Now, TikTok can feel a bit like an iteration of the Home Shopping Network, with ordinary people hawking the stepper that’ll get you snatched for summer or that matching knit set that comes in every color.

If the dream the MLMs sold over the last decade was to build a business by getting women to recruit their friends and family to join, the dream affiliate marketing sells is creating influencer-style passive income streams from the comfort of your own home. Sellers don’t even have to hold any inventory; it’s all facilitated through the app’s shop. While the model involves significantly less financial risk than the traditional MLM model, it still feeds on women’s ambitions in an insidious way to market its products. It’s still possible to get lucky playing TikTok’s algorithm game, but an ordinary person’s chances of becoming a moneymaking influencer look more like playing a slot machine—at the end of the day, it’s still gambling.

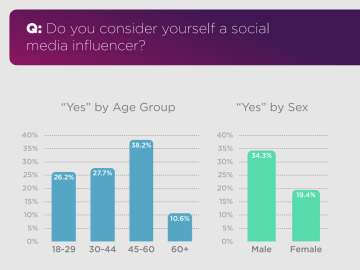

Some sellers are already saying the quiet part out loud. A user with the handle @drwendy_physicaltherapy credits R&F for helping her become comfortable posting videos on TikTok: “I know there’s not a perfect company, but Rodan & Fields was a game changer for me and it makes me sad. But I’m a TikTok influencer and affiliate sales is TikTok. It is social media. So social network—MLM—is now really all of this. So all of this is the new MLM.”

If you liked this column, smash that subscribe button, hit the bell to be notified, and check out the link to my Amazon shop. And if you’re an influencer who wants to get in touch with me for a story, my email is alex@defector.com. See you next time.