More than a decade after a national study found that Henrico Schools had the highest disparity nationally between the suspension rates of Black and white students, recent data shows that significant racial disparities continue to exist within the school system when it comes to school discipline and punishment.

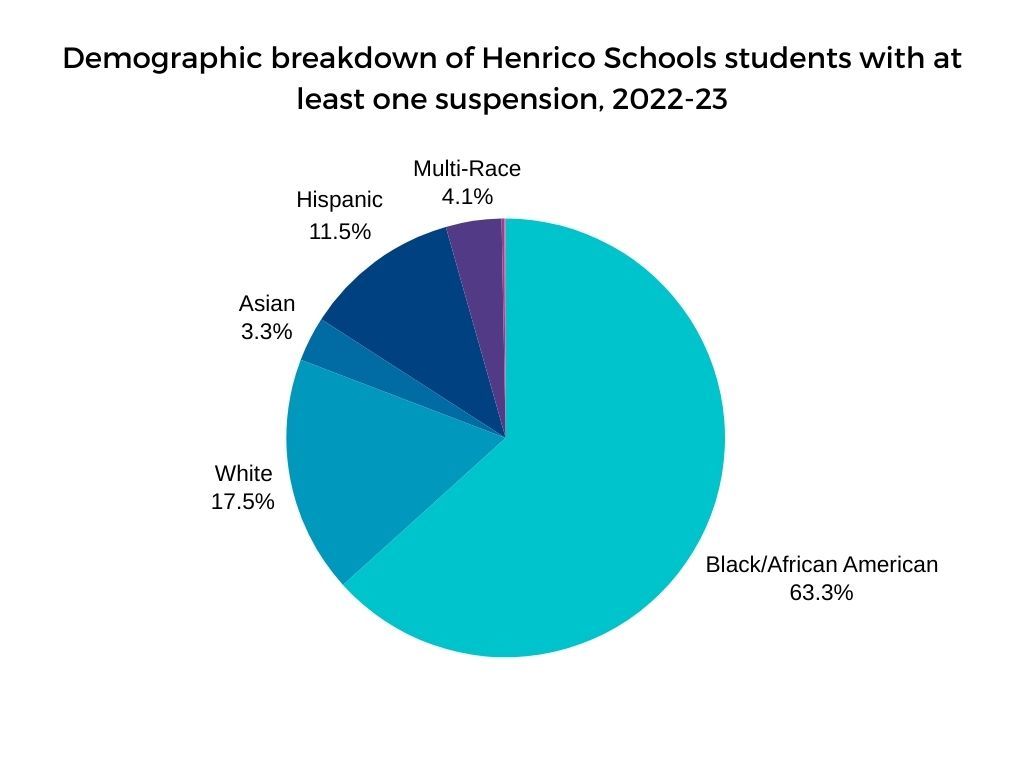

Although Black students comprise only one-third of Henrico Schools’ student population, they accounted for 63% of the students who were suspended at least once during the 2022-2023 school year, according to data provided to the Henrico Citizen by the school system. By contrast, white students (who also comprise about one-third of the student population), made up only 18% of students who were suspended.

The disparity was even more evident among students who received out-of-school suspensions (those given for more serious behavioral offenses) during the school year – 70% of whom were Black.

“The racial disparity is super concerning,” Henrico NAACP president Monica Hutchinson told the Citizen. “That tells me something’s not working, that we are missing a huge piece of the puzzle.”

Schools with majority Black student populations also had the highest suspension rates in Henrico during the 2022-23 school year, according to the data.

At Varina’s John Rolfe Middle, which is 83% Black, nearly half of the student body was suspended at least once during the 2022-2023 year. At Fairfield Middle, which is 89% Black, one-third of the student body was suspended.

At Varina’s John Rolfe Middle, which is 83% Black, nearly half of the student body was suspended at least once during the 2022-2023 year. At Fairfield Middle, which is 89% Black, one-third of the student body was suspended.

All but one of the seven schools that suspended more than 20% of their student body in 2022-2023 are located in the Varina and Fairfield districts. Henrico School Board Chair Alicia Atkins, who represents the Varina District, said that broader issues in those communities – higher poverty rates, less access to healthcare, and fewer recreational opportunities – contribute to more discipline problems in the schools.

“The issue of racial disparities in school discipline cannot be divorced from the broader socioeconomic context that surrounds the schools,” she said. “In other words, what happens within schools may be indicative of what’s happening around schools. And even with those obstacles, what really shines through is the resilience and the potential of our students.”

But, HCPS leaders recognize that there is still work to do on ensuring that behavior rules are implemented consistently and fairly throughout the county, Fairfield District school board representative Ryan Young said.

“Yes, the suspension numbers are what they are,” he said. “I just want to make sure I’m clear on this – we’re never going to say that teachers should stop addressing student behaviors or [stop] sending referrals about students. But, and I can’t say this any louder, we want to make sure that all students are receiving similar consequences for their actions, regardless of their race.”

The higher percentage of Black students receiving suspensions could point to a disconnect between school staff and the student populations they serve, Hutchinson said. School staff and leaders may not recognize the cultural differences between different student groups and be overly punitive to students who are more loud or animated.

“Some issues can be resolved without suspending a child,” Hutchinson said. “It’s those cultural differences. It’s those little things that maybe a child raised their voice, but they’re not necessarily raising their voice because they’re going to escalate. It could come down to maybe the tone wasn’t what someone wanted it to be.”

* * *

* * *

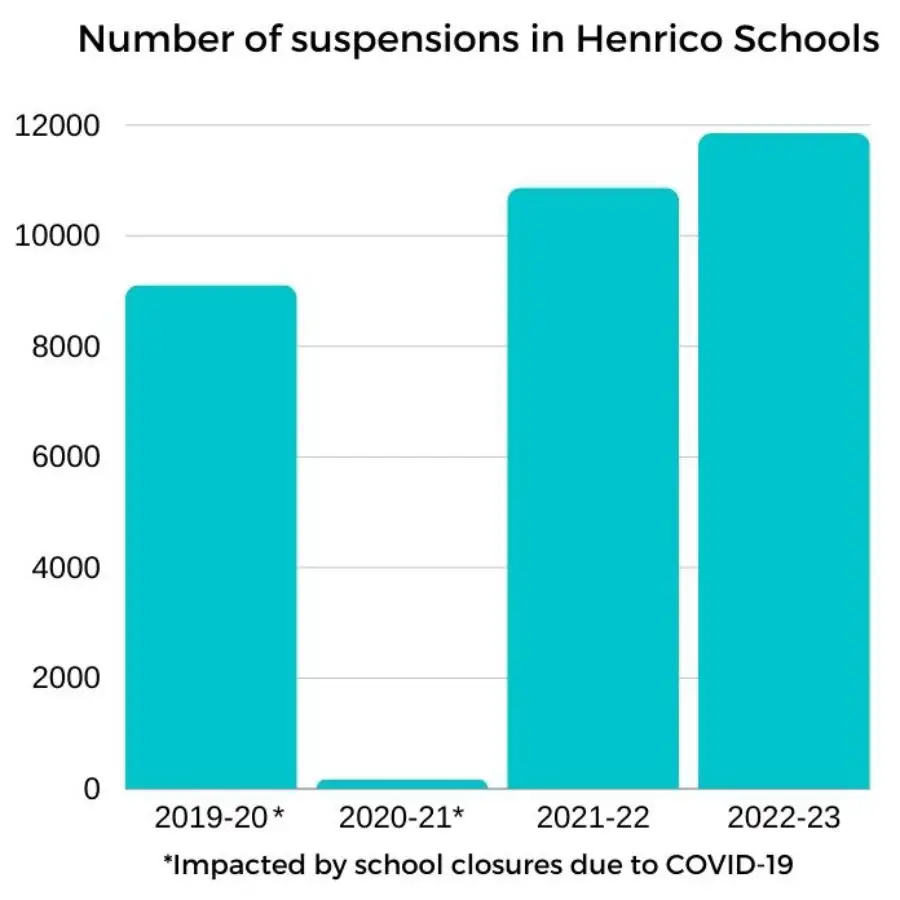

HCPS also handed out a higher number of suspensions – not just for Black students but for all student groups – in 2022-2023 compared to previous years.

Almost 12,000 suspensions were implemented in 2022-2023, while a little more than 9,000 were implemented in the COVID-19-shortened 2019-2020 school year. Since 2019, suspensions rates have been steadily rising each year, with 2020-2021 being the exception because of school closures due to COVID.

Around 5,400 HCPS students received at least one suspension in 2022-2023, meaning that some students were suspended more than once.

Hutchinson said the increase is worrisome. With such a high number of suspensions handed out, students may begin to view the punishment as “less of a big deal,” she said, making them less effective in changing behavior. And for students who have working parents or little adult supervision at home, removing them from the school could simply exacerbate behavioral issues.

“At the end of the day, kids can’t learn if we don’t have them in school,” she said. “When I was growing up, if somebody got suspended that was a pretty big deal. But now, when you do it frequently, you do desensitize the kids to a suspension and to what it’s supposed to mean.”

William Noel, the director of HCPS’s Disciplinary Review Hearing Office, said he witnessed a large spike in misbehavior, particularly fighting between students, when schools opened back up following COVID. He believes that many of the fights that would have occurred if students weren’t in virtual learning instead manifested the next year when students came back in-person.

“When we came back from COVID, full-throttle back, the suspensions and expulsion recommendations skyrocketed. I had a recommendation for expulsion the second week of school” he said. “And what it is, in my opinion, is when students were out in virtual [learning], all of the neighborhood beefs – what manifests unfortunately in school – didn’t happen because they were virtual.”

Noel, who handles more severe behavior violations that could lead to long-term suspensions (out-of-school suspensions for more than 10 days) or even expulsions, said that he views community issues and “beefs” as the number one driver of misbehavior in schools, leading to a rise in suspensions. In some cases, parents and families have even exacerbated the fighting by encouraging their children to “settle the score.”

“Community issues is probably the number one thing that I see,” he said. “And I would not believe it, but some of the parents are actually contributing to issues that we’re seeing. They’re saying, ‘This is not over, you’re going to finish this,’ or actually driving to the other people’s neighborhoods to try to settle this.”

Henrico Schools recorded about 14,500 behavior violations in 2022-2023 that could be grounds for suspension – either automatically or if the violation is repeated. The school division categorizes offenses from less severe, starting with violations such as “excessive noise” and “interrupting a class,” to more severe, such as “assault with firearm” and “aggravated sexual battery.”

(Click here to view the demographic breakdown of 2022-2023 suspensions.)

(Click here to view the number of suspensions from each year since 2019.)

(Click here to view suspension rates at each school in 2022-2023.)

The most common violation reported was “refusal to to comply with requests of staff in a way that interferes with the operation of the school,” which falls under the less severe “behaviors related to school operations” category.

Fighting between students was also a recurrent problem; the next most frequent violations were “fighting that results in no injury” and “engaging in reckless behavior that creates risk of injury,” which both fall under the more severe “behaviors of a safety concern” category.

HCPS aims to use suspensions, especially out-of-school suspensions, as a “last resort,” Noel said. Lesser offenses such as talking back, shouting, or pushing, are more likely to result in a short in-school suspension or restorative practices such as a conflict resolution meeting between students, a peer circle, or a call home or meeting with the family.

“Our goal is to help students make better decisions, and not exclusionary practices,” Noel said. “If it’s something lesser, like pushing and shoving, verbal back and forth, once upon a time they’d get an out-of-school [suspension], but now it would probably land them an in-school [suspension] or some sort of restorative practice.”

However, more severe behavior violations, such as possession of a firearm or weapon, are “non-negotiable” for the division, Noel said, and require more severe punishments.

“I’m all for restorative practices, but for somebody to get to my office, either restorative practices don’t work at this point or the infraction is so severe that it needs to come forward to me,” he said. “We absolutely give every threat or every fight or every instance the absolute attention it deserves.”

* * *

The issue of racial disparities in discipline is not new to Henrico Schools. In 2012, a national study by the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at UCLA reported that no school system in Virginia had a greater disparity between the suspension rates of Black and white students than Henrico. The study also concluded that Henrico had one of the highest suspension-rate disparities in the nation involving Black students with disabilities.

During the following years, HCPS worked to make the division’s Code of Student Conduct less punitive and less exclusionary to certain demographics, Noel said, removing any “gender-specific” or “cultural-specific” language.

Henrico Schools also implemented new positive behavior interventions and support (or PBIS) programs in an effort to use more restorative practices in place of punitive discipline measures. Currently, 67 of Henrico’s 75 schools have a PBIS program in place, led by a PBIS coach – typically a teacher taking on the additional duties.

PBIS does not replace traditional discipline measures, said Matthew Jones, who directs Henrico’s PBIS program. Instead, each school works to develop school-wide behavioral expectations and model them for students, while also teaching students that certain behaviors will lead to consequences.

“We’re going to teach you expectations, we’re going to model those expectations, but if you do not meet those expectations, there are consequences,” Jones said. “And it’s about how are we building relationships so that we can meet our students where they are.”

HCPS also has worked to implement diversity and equity training for staff, HCPS Communications Director Eileen Cox said, encouraging staff to build personal relationships with their students and families.

“Our staff does go through culturally responsive training and education models through the Office of Equity, Diversity and Opportunity,” Cox said. “There is a focus on relationship building between staff and students, because if you understand where a student is coming from, what circumstance that they’re coming to school from, or what’s going on for them on a personal level, then you might understand their behaviors a little better.”

But inconsistency in enforcing rules still remains a countywide problem, Noel said. How administrators respond to and discipline misbehavior varies from school to school, causing some schools to have suspension rates nearing 50% and other schools to suspend less than 1% of students.

“This is my tenth year in Henrico, so I’ve worked with schools and I know which ones are going to say, ‘I’m going to work with this kid, I want to put these supports and interventions in place,’ and then there are some that will say, ‘this is the first time and I suspended them for X amount of days,’” he said.

School board members also called for more consistency in school discipline at a meeting this past spring, encouraging HCPS Superintendent Amy Cashwell to make consistent enforcement of behavioral rules a focus for HCPS leaders.

Henrico also is working to provide more wraparound supports for students, which will help tackle the underlying community and mental health issues that often lead to misbehavior, Atkins said. The division recently promised to invest a total of $17.8 million over the next five years into a new comprehensive mental healthcare program, Henrico CARES, which would staff schools with more mental health professionals and better connect families to community providers.

“What we’re doing is adding resources. We are adding counselors, we have a multi-million dollar program with Henrico CARES, that is turnkey. Behavior is mental, and we know we have a mental health crisis with our young people,” Atkins said. “And all of these things that I mention are going to help schools like John Rolfe and every single school in our district.”

But HCPS will need the support of students’ families and communities to tackle the division’s discipline issues, Jones said.

“We can’t do it within the division alone. It takes the parents, it takes the community, businesses, it takes the leaders within the community to say enough is enough,” he said. “And we have to work together to make sure everybody understands the sense of urgency that we must have to make this change.”

* * *

Liana Hardy is the Citizen’s Report for America Corps member and education reporter. Her position is dependent upon reader support; make a tax-deductible contribution to the Citizen through RFA here.