From left, Dorianne Samuels and Felicity Kostakis, event chairs of the Greenwich Arts Council luncheon; Eric Ripert, chef and co-owner of Le Bernardin; and Cristin Marandino, editorial director of Greenwich magazine. Photograph by Cara Gilbride/Greenwich magazine.

“Creativity and spirituality are different,” said Eric Ripert, chef and co-owner of Le Bernardin restaurant in Manhattan. “I’m not sure I can see a connection.”

He was speaking with Cristin Marandino, editorial director of Greenwich magazine, at a May 29 luncheon at Brae Burn Country Club in Purchase benefiting the Greenwich Arts Council. Le Bernardin and the Moffly Media publication co-sponsored the luncheon, along with BNY Mellon and Blue Ribbon Fish Co. in the Bronx, which supplied the delicate sauce for the melt-in-your-mouth salmon at the luncheon – the same salmon served at Le Bernardin. (Blue Ribbon is owned by Greenwich resident David Samuels, who was among the 134 guests at the luncheon and whose wife, Dorianne, served as event co-chair with artist Felicity Kostakis.)

But perhaps there is a connection between Ripert’s creative success at Le Bernardin – possessor of the maximum three Michelin stars as well as four New York Times stars for more than three decades – and his Buddhist practice, represented by the mala meditation beads he wears wound around one wrist. Marandino, who visited Le Bernardin’s kitchen recently, said it was a place of fluid serenity despite the hustle and bustle of 75 cooks.

That serenity contrasts, Ripert told the attendees, with the physical and verbal abuse he witnessed and experienced as a young chef in France, where he was born into a French-Italian household of comforting meals made by his grandmothers and mother. The young Eric loved to eat their food and longed to cook. Soon he was going to the market, helping in the kitchen, reading cookbooks – and neglecting his studies.

Eventually, school officials would call him and his mother on the carpet to tell them the 15-year-old Eric would have to go to vocational school.

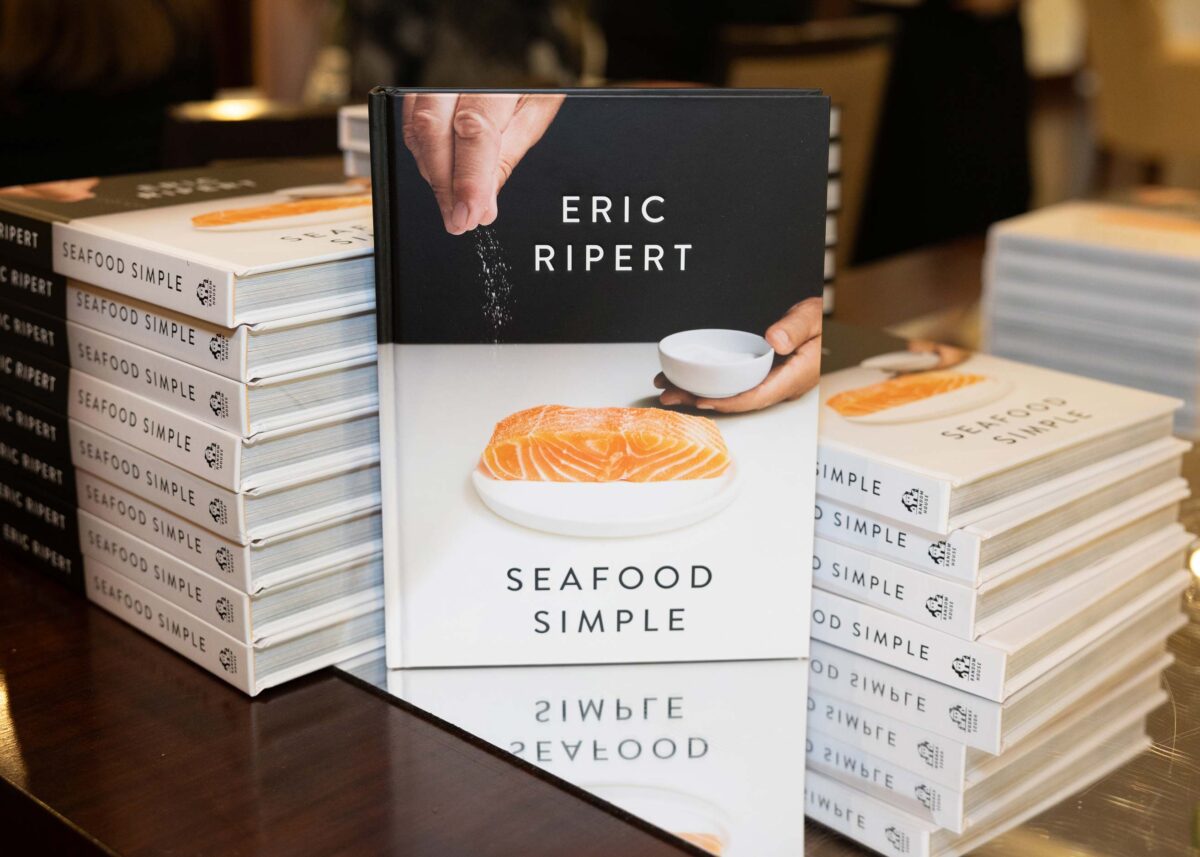

Guests received a signed copy of Ripert’s latest book, “Simple Seafood.” Photograph by Cara Gilbride/Greenwich magazine.

Guests received a signed copy of Ripert’s latest book, “Simple Seafood.” Photograph by Cara Gilbride/Greenwich magazine.

“I had to look sad, of course, but I was delighted,” Ripert, a humorous storyteller, said of the opportunity to study cooking in Perpignan in his native Southern France. Two years later, he was off to Paris to work at La Tour d’Argent, an historic restaurant, and then Jamin. The kitchens of 1980s Paris were tough places, Ripert said, where chefs ruled as dictators and young staffs were mistreated. At first, Ripert – who came to the United States in 1989 and served as sous chef at the Watergate Hotel’s Jean Louis Palladin before moving two years later to New York City, where he was briefly David Bouley’s sous chef – thought he had to emulate that toughness. But then he realized “anger is a weakness.” It was, Ripert said, his “duh” moment.

“I immediately changed my mindset. We don’t need to have this kind of abuse. I direct my team to have respect and compassion.” Not like, say, Gordon Ramsey (“Hell’s Kitchen”), added Ripert, who said he himself does not curse.

Besides dignity and understanding in the workplace, Ripert said you have to listen to what your patrons want. Le Bernardin’s tuna carpaccio with foie gras is a signature dish – one that disappeared from the menu but only briefly as there was about to be a second French Revolution among the clientele. (For the courageous, tuna carpaccio appears in “Seafood Simple” (Random House, $35, 286 pages), the latest of Ripert’s seven cookbooks, a signed copy of which each of the luncheon guests received and which begins: “Cooking seafood is, in truth, not that simple.”)

Ripert recognized that not being able to savor the tuna carpaccio at Le Bernardin would be like finding certain songs absent from the playlist at a Rolling Stones concert.

“You’re going to be like, ‘Mick, no ‘Satisfaction’?’”

While it’s great to experiment in business, he added, you also need to know when thinking outside the box represents only a noble failure and move on. Hence fish with strawberries: Ripert, who said creativity comes to him in a flash and then the tastebuds take over, worked and worked on that recipe. In the end, it was edible, he said, but only just. And that’s not good enough for him: “Food has to be delicious, not just edible.”

In making that food, you have to be eyes on the process rather than the prize or, in this case, the Michelin and Times stars. If all you’re thinking about is the Oscar or the Grammy, you’ll never give a great performance, added Ripert, who finds a lot of commonality between food and the arts.

Given his additional success as a chef and restaurateur with the Aldo Sohm Wine Bar in midtown and Blue by Eric Ripert at The Ritz-Carlton, Grand Cayman, and on Bravo’s “Top Chef,” it’s not surprising that Ripert sees life like a pie – a third for family, a third for work and a third for self, with each refreshing the creative juices of the others. (“Seafood Simple” salutes “the hard work, passion and dedication of the team and the unconditional love of my family.”)

The third for self would include not only a recent trip to Korea – “South Korea,” Ripert emphasized to laughter – to forage for vegetables with Buddhist monks in a forest, “an exercise in mindfulness”; and his friendship with the late chef, author and documentarian Anthony Bourdain, with whom he ate his way across New York City. Said Ripert: “We had fun together.”

But also in the “self” slice of the pie, Ripert might put his role as vice chair of City Harvest, which he joined in 1995 and which continues to rescue fresh produce and distribute it to the city’s food insecure, roughly 1.2 million people. That’s one billion pounds of food over 40 years.

It’s a reflection of what Ripert said was his favorite word – “love.”

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/cmg/TMIMSW765BEYJEPLH7Q3DMRVWY.jpg?w=360&resize=360,270&ssl=1)